C for the Charm of a piano

To share his thoughts on Beauty, French designer Patrick Jouffret chose to talk about objects created by humans to fulfill their dreams. For Patrick, these objects go beyond fashion and status. They make something functional beautiful, mark chapters in our history, and show how our needs have evolved. Through this subjective selection, which he presents in the form of an alphabet book, Patrick explores the hidden dimensions of these objects – dimensions that make them unique, timeless, and essential. After discovering the letter B for Bicycle, let’s continue this serie with the letter C for… the Charm of a piano!

A grand piano, by its very size and weight, is a piece of furniture in itself whose design has evolved to follow the decorative trends of the time. From Cristofori’s pianoforte to the more recent Pleyel models, a piano speaks of its era through its style: the shape of the case, the size of the legs and pedal holders, the details around the edges or on the music rack, the ornamental details and decoration on the sides, or the way in which the wood is finished.

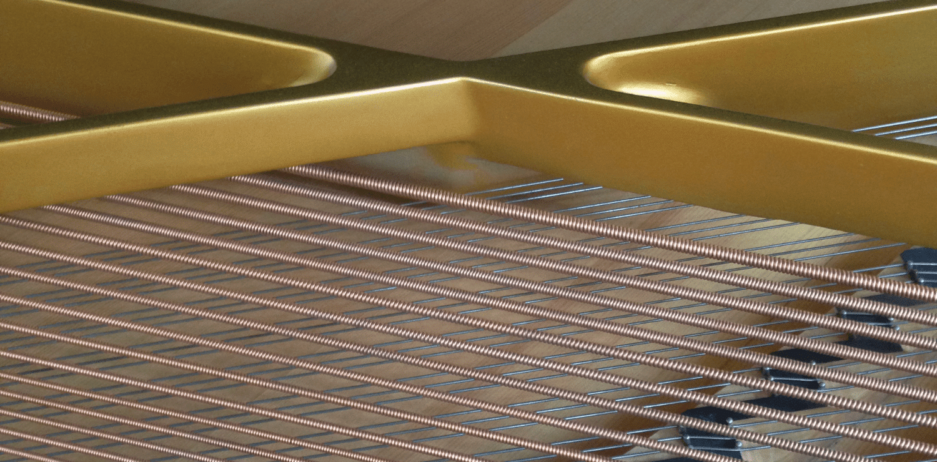

But inside the case of a piano is a thing of timeless beauty: the cast-iron frame. Born at the same time as the Romanticism movement, it gives the instrument more sound power, while also extending its life. Because the piano frame could not be seen from the outside, its designers were able to focus on the essential. This involved defining the ideal structure to withstand the tremendous tension of and resonance from the strings, based on the materials chosen; anticipating any deformations during the cooling process; and adapting to the shape of the case. Any choices made regarding the shape or the cut-out sections were aimed at making the structure as light as possible.

This unseen beauty also testifies to the modernity of the techniques used during the Romantic period, when innovation was not exactly embraced… Two visions of the world cohabit within a single instrument. One is about depiction and appearance. The other is about performance and science. The outer beauty and the inner functionality.

The fact is that years later, we are struck by the modernity of these forms, which were completely devoid of stylistic intentions. It seems that often a good design is also the simplest… The artisans of the time did, of course, appreciate good craftsmanship and would pay great attention to the finishing details of the frames, but they did not have a responsibility to impress. Any tension in the forms is neither beautified nor radicalized. It is simply treated as it should be.

The curved lines are there to strengthen. The cut-out sections are there to control the resonance or give it more weight (lighten the framework without losing efficiency). In general, simply the name of the manufacturer, in relief, and the outline inferred by the wooden frame, attest to their time.

In his book Patterns in Nature, Peter S. Stevens shows to us that the shapes and structures all around us are strangely limited. The milk foam on the surface of an espresso resembles the shape of a galaxy. Rivers and their tributaries work in the same way as our arteries and veins. The harmony and beauty of the natural world come from these limitations.

The tension bars of the cast-iron frame are like the branches of a tree that become thinner the further they are from the trunk, putting out leaves to absorb as much light as possible. A cosmic truth that we find difficult to understand is there, right in front of our eyes. Perhaps it becomes clear when we stop trying to create beauty and

The harmony and beauty of the natural world come from these limitations.

The tension bars of the cast-iron frame are like the branches of a tree that become thinner the further they are from the trunk, putting out leaves to absorb as much light as possible. A cosmic truth that we find difficult to understand is there, right in front of our eyes. Perhaps it becomes clear when we stop trying to create beauty and let our hands be guided by the purity of mathematics.